wikipedia

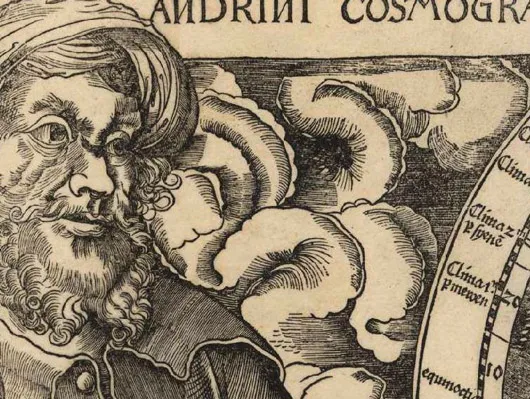

The first world map to include the Western Hemisphere was drawn in 1507 by an Alsatian cartographer named Martin Waldseemuller. Its initial printing ran a thousand copies, of which only one complete version—purchased recently by the Library of Congress for $10 million—is known to exist. Even in the tantalizingly low-resolution copies available on the Internet, Waldseemüller’s map is a thing of beauty, brilliantly illustrated and full of written descriptions and details about seas and cities and rivers

Nestled in the scrollwork and filigree at the top edge of the map are portraits of two men: on the left, there’s Ptolemy, the great Greek geographer, presiding over an inset map of the Old World. And on the right, an Italian upstart—not Christopher Columbus but Amerigo Vespucci—gazes toward the great South Sea, where floats the continent that for the first time bears his name: America, distorted by Waldseemüller’s haphazard projection into the shape of an enormous chicken tender. Due south of Amerigo’s visionary face, amidst rivers and lakes in the general vicinity of Tibet, the careful reader of Latin may find words to the following effect: “This is the land of the good king and lord, known as Prester John, lord of all Eastern and Southern India, lord of all the kings of India, in whose mountains are found all kinds of precious stones.” The spot is marked, not by the expected X, but with the sign of the cross.

Prester John was not, despite what you might think from the name, a circus performer or the founder of a chain of fried-food restaurants. Nor was he a magician, though he did have the trick of vanishing only to reappear in unexpected places. And if his name, once you say it a few times, seems at once both obscure and familiar, there may be a reason. For nearly half of the last millennium, Prester John was a genuine celebrity in Western Europe: the mysterious ruler of an impossibly rich and powerful kingdom just over the horizon, somewhere in Asia, or maybe Africa. He was, as the saying goes, the stuff of legends, like Elvis or Brando or the Sultan of Brunei. He was wealthy, he was powerful, and—best of all—he was a Christian

His first authenticated appearance is in the twelfth-century chronicle of Otto of Freising, who tells of the military victories of a priest-king living in the Far East. This king, known as Prester John, had defeated a combined force of Persians, Medes, and Assyrians in a glorious three-day battle and then marched to the aid of Jerusalem, which had lately been recaptured by Saracen Muslims. The journey didn’t go well for Prester John. He marched his army to the Tigris and, unable to cross it, followed the river north in hopes it would freeze during the winter. After waiting several years for the promised ice to appear, he decided that the climate was too temperate, and, his army decimated “on account of the weather to which they were unaccustomed,” the priest-king headed home. Though not much for boats or bridges, Prester John was nonetheless, even in this early account, an intriguing character: “He is said to be a descendant of the Magi of old,” Otto’s chronicle reports. “He governs the same people as they did and is said to enjoy such glory and such plenty that he uses no scepter save one of emerald.”

A couple of decades later, the story got even more impressive. In 1165, copies of a letter from Prester John to the emperor of Byzantium started making the rounds in Europe. The letter, reconstructed from later copies, began something like this: “I, Johannes the Presbyter, Lord of Lords, am superior in virtue, riches and might to all who walk under Heaven,” and went on from there. Seventy-two kings paid him tribute. Thirty thousand subjects dined daily at his table. When he rode into war, he was proceeded by three crosses of gold. On other occasions, he went forth behind a single cross of plain wood—that he might recall the humble death of Jesus Christ, whom he served

As for the kingdom he ruled, it was a storehouse of wonders: elephants, dromedaries, mute griffins, wild oxen, and wild men. There were pygmies, giants, Cyclopes and their wives, not to mention a more or less complete collection of natural resources: emeralds, sapphires, carbuncles, topazes, chrysolites, onyxes, beryls. There was a plant whose very presence in the realm frightened away demons. A spring, which, if you drank from it three times, would keep you 30 years old for the rest of your life. And since it wouldn’t be the East without spices, of course there was lots of pepper. Now it seems obvious enough, given certain details, that the letter was at least partly fictitious. And, as the novelist Evan S. Connell notes in his delightful essay on Prester John (collected most recently in The Aztec Treasure House), the leading men of Europe—being no more or less gullible than we—were doubtful even at the time. A translation of the letter by one of Richard Lionheart’s knights included a caveat familiar to anyone who has received a forwarded e-mail: This might not be true, but I thought you’d want to read it anyway. The letter was most likely seen as a veiled dressing-down of the rulers of the day, or perhaps as an attempt to revitalize the Crusades with the hope of an inter-empire coalition. Nevertheless, twelve years later Prester John and his epistle were still on everyone’s minds, so to quiet the murmurings and instruct the masses Pope Alexander III penned a response praising John for his apparent piety and gently restating the Christian duty of submission to papal authority. Sealed and signed, the letter was entrusted to the pope’s personal physician who, as Connell dryly notes, “obediently marched off in the direction of Asia and right off the pages of history.”

Over the next century, a handful of European travelers returned from Asia with news of Prester John. A former pupil of Saint Francis of Assisi, John de Piano Carpini, went east in 1245 to scout out Asia and see if the Tartar king was a Christian. He arrived at the Mongol court just in time to attend the coronation of Genghis Khan’s grandson Kuyuk. A year and a half later, he made it home with a letter from the khan to the pope: “Whoever recognizes and submits to the Son of God and Lord of the World, the Great Khan, will be saved. Whoever refuses will be annihilated … ” On the brighter side, Brother Carpini did mention having heard of a black Saracenic king named Prester John who ruled somewhere in India

A few years later, another salvo of Franciscans—including the chronicler William of Rubruck—was launched eastward. Upon arriving at the court of Mangu Khan (Kuyuk’s successor), they were surprised to find a number of Christians already there: a Hungarian translator, a Parisian goldsmith, an Armenian monk, and a Greek knight. Better still, the khan’s interpreter and his grand secretary—“whose advice they nearly always follow”—were also Christians, as had been the khan’s favorite wife until her death. A few days into the Franciscans’ visit, Sergius, the Armenian monk, reported that Mangu himself had agreed to be baptized. Excited but a bit skeptical, William asked to be invited to the ceremony, but he was only summoned when the Armenian and the khan’s Nestorian priests were on their way out, cross and censor and Gospels in hand. Sergius assured him that the baptism had gone through, and that although the khan was alternately attended by Christian, Muslim, and pagan priests, he really only believed the Christians. In the end, though, Mangu’s opinions proved to be, from the Franciscans’ point of view, depressingly pluralistic: “As God gives us the different fingers of the hand,” Mangu said, “so he gives to men several paths. God gives you the Scriptures, and you Christians keep them not … He gave us diviners, we do what they tell us, and we live in peace.” As for the Nestorian Christians, who were descendants of a sixth-century missionary effort launched by the patriarch of Constantinople, William had his concerns. They seemed unfamiliar with Scripture, a few of their priests embraced the dualistic Manichean heresy, and besides all that they drank too much, ate meat on Fridays, and feasted and washed themselves in the manner of their Muslim neighbors.

William and his companions longed to stay and minister to both the Nestorians and the non-Christians at Mangu’s capital, but once the weather was sufficiently warm, the khan sent them packing. After a year of hard travel, the remnants of the Franciscan expedition reached the Christian fortress of Acre, where William penned a letter to the French king reporting what he’d seen and heard. The news must have been disappointing: there were Christians in the East, but not of the proper sort; there were great kings, but the prospects for alliances with Christendom seemed unlikely. And Prester John? William said he had ruled in Central Asia, but had been destroyed by the Tartars generations ago. Twenty-five years later another traveler, a fellow named Marco Polo—one with, it should be noted, fewer qualms than William of Rubruck about embellishing his stories—reported much the same thing thing: Prester John was dead. To which Europe replied, “Long live Prester John!”

Most of us learned in school that medieval Europeans wanted spices because their food was so bad. But maggoty meat and moldy bread don’t fully explain the depth of the Western obsession with Eastern flavors. The social historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch notes that due to their cost, spices were most readily available to the rich—those who could also afford fresh or properly preserved foodstuffs. For wealthy Europeans, spices didn’t just make the meal palatable: they made the meal. Many medieval recipes read as if they’d been lifted from a modern Indian cookbook: large quantities of cloves, cinnamon, pepper, almonds, raisins, all in a single dish. At times spices were even a separate course—passed around on a tray and consumed a pinch at a time

Spices were so desirable, Schivelbusch says, because they offered Europeans “tastes of paradise”—flavors from a world outside their own. Spices provided a new and lush form of stimulation, a sign of the eternal, the transcendent, the wonderful. Contemporary illustrations of heaven often depicted spices and exotic plants. This growing awareness of and desire for goods from the East was born, somewhat ironically, out of the Crusades, where cultural domination mixed with cultural exchange. For soldiers, suppliers, and hangers-on, crusading amounted to a large-scale exposure to the products of the non-Western world. A motto of the times might have been Come for the Holy War, stay for dessert! So Europeans of the era may have found themselves feeling a bit conflicted. The East was the source of all sorts of wonders and exotica, the wellspring of the stuff of heaven. But the very region that seemed a sign of paradise was populated by peoples hostile, or at best indifferent, to the faith of the Western Christians. Could one condemn the East but still enjoy its products, or were all those tasty spices tainted by heresy? The answer to this conundrum may have manifested itself, among other ways, in the chaste but shadowy figure of—you guessed it—Prester John.

Which brings us to Sir John Mandeville, a fourteenth-century English knight who spent 34 years travelling “throughout Turkey, Armenia the little and the great; through Tartary, Persia, Syria, Arabia, Egypt the high and the low; through Lybia, Chaldea, and a great part of Ethiopia; through Amazonia, Ind the less and the more … and throughout many other Isles.” Around 1366, he penned, in Latin, French, and English, a widely read account of his journeys. Sir John’s narrative, like the man himself, seems to have been a ghostwriter’s fabrication—a means of collecting and connecting various reports, stories, myths, and fables from the Orient. Mandeville’s Travels devote an entire chapter to Prester John and his kingdom, incorporating most of the content of the original letter to the Byzantine emperor plus all sorts of new and captivating material—much of which gives credence to the idea that Prester John was beloved as proof that one could enjoy the wonders of the East and still be a pious Christian. Here, for instance, is Mandeville’s account of the royal bedroom:

wikipedia

The first world map to include the Western Hemisphere was drawn in 1507 by an Alsatian cartographer named Martin Waldseemuller. Its initial printing ran a thousand copies, of which only one complete version—purchased recently by the Library of Congress for $10 million—is known to exist. Even in the tantalizingly low-resolution copies available on the Internet, Waldseemüller’s map is a thing of beauty, brilliantly illustrated and full of written descriptions and details about seas and cities and rivers

Nestled in the scrollwork and filigree at the top edge of the map are portraits of two men: on the left, there’s Ptolemy, the great Greek geographer, presiding over an inset map of the Old World. And on the right, an Italian upstart—not Christopher Columbus but Amerigo Vespucci—gazes toward the great South Sea, where floats the continent that for the first time bears his name: America, distorted by Waldseemüller’s haphazard projection into the shape of an enormous chicken tender. Due south of Amerigo’s visionary face, amidst rivers and lakes in the general vicinity of Tibet, the careful reader of Latin may find words to the following effect: “This is the land of the good king and lord, known as Prester John, lord of all Eastern and Southern India, lord of all the kings of India, in whose mountains are found all kinds of precious stones.” The spot is marked, not by the expected X, but with the sign of the cross.

Prester John was not, despite what you might think from the name, a circus performer or the founder of a chain of fried-food restaurants. Nor was he a magician, though he did have the trick of vanishing only to reappear in unexpected places. And if his name, once you say it a few times, seems at once both obscure and familiar, there may be a reason. For nearly half of the last millennium, Prester John was a genuine celebrity in Western Europe: the mysterious ruler of an impossibly rich and powerful kingdom just over the horizon, somewhere in Asia, or maybe Africa. He was, as the saying goes, the stuff of legends, like Elvis or Brando or the Sultan of Brunei. He was wealthy, he was powerful, and—best of all—he was a Christian

His first authenticated appearance is in the twelfth-century chronicle of Otto of Freising, who tells of the military victories of a priest-king living in the Far East. This king, known as Prester John, had defeated a combined force of Persians, Medes, and Assyrians in a glorious three-day battle and then marched to the aid of Jerusalem, which had lately been recaptured by Saracen Muslims. The journey didn’t go well for Prester John. He marched his army to the Tigris and, unable to cross it, followed the river north in hopes it would freeze during the winter. After waiting several years for the promised ice to appear, he decided that the climate was too temperate, and, his army decimated “on account of the weather to which they were unaccustomed,” the priest-king headed home. Though not much for boats or bridges, Prester John was nonetheless, even in this early account, an intriguing character: “He is said to be a descendant of the Magi of old,” Otto’s chronicle reports. “He governs the same people as they did and is said to enjoy such glory and such plenty that he uses no scepter save one of emerald.”

A couple of decades later, the story got even more impressive. In 1165, copies of a letter from Prester John to the emperor of Byzantium started making the rounds in Europe. The letter, reconstructed from later copies, began something like this: “I, Johannes the Presbyter, Lord of Lords, am superior in virtue, riches and might to all who walk under Heaven,” and went on from there. Seventy-two kings paid him tribute. Thirty thousand subjects dined daily at his table. When he rode into war, he was proceeded by three crosses of gold. On other occasions, he went forth behind a single cross of plain wood—that he might recall the humble death of Jesus Christ, whom he served

As for the kingdom he ruled, it was a storehouse of wonders: elephants, dromedaries, mute griffins, wild oxen, and wild men. There were pygmies, giants, Cyclopes and their wives, not to mention a more or less complete collection of natural resources: emeralds, sapphires, carbuncles, topazes, chrysolites, onyxes, beryls. There was a plant whose very presence in the realm frightened away demons. A spring, which, if you drank from it three times, would keep you 30 years old for the rest of your life. And since it wouldn’t be the East without spices, of course there was lots of pepper. Now it seems obvious enough, given certain details, that the letter was at least partly fictitious. And, as the novelist Evan S. Connell notes in his delightful essay on Prester John (collected most recently in The Aztec Treasure House), the leading men of Europe—being no more or less gullible than we—were doubtful even at the time. A translation of the letter by one of Richard Lionheart’s knights included a caveat familiar to anyone who has received a forwarded e-mail: This might not be true, but I thought you’d want to read it anyway. The letter was most likely seen as a veiled dressing-down of the rulers of the day, or perhaps as an attempt to revitalize the Crusades with the hope of an inter-empire coalition. Nevertheless, twelve years later Prester John and his epistle were still on everyone’s minds, so to quiet the murmurings and instruct the masses Pope Alexander III penned a response praising John for his apparent piety and gently restating the Christian duty of submission to papal authority. Sealed and signed, the letter was entrusted to the pope’s personal physician who, as Connell dryly notes, “obediently marched off in the direction of Asia and right off the pages of history.”

Over the next century, a handful of European travelers returned from Asia with news of Prester John. A former pupil of Saint Francis of Assisi, John de Piano Carpini, went east in 1245 to scout out Asia and see if the Tartar king was a Christian. He arrived at the Mongol court just in time to attend the coronation of Genghis Khan’s grandson Kuyuk. A year and a half later, he made it home with a letter from the khan to the pope: “Whoever recognizes and submits to the Son of God and Lord of the World, the Great Khan, will be saved. Whoever refuses will be annihilated … ” On the brighter side, Brother Carpini did mention having heard of a black Saracenic king named Prester John who ruled somewhere in India

A few years later, another salvo of Franciscans—including the chronicler William of Rubruck—was launched eastward. Upon arriving at the court of Mangu Khan (Kuyuk’s successor), they were surprised to find a number of Christians already there: a Hungarian translator, a Parisian goldsmith, an Armenian monk, and a Greek knight. Better still, the khan’s interpreter and his grand secretary—“whose advice they nearly always follow”—were also Christians, as had been the khan’s favorite wife until her death. A few days into the Franciscans’ visit, Sergius, the Armenian monk, reported that Mangu himself had agreed to be baptized. Excited but a bit skeptical, William asked to be invited to the ceremony, but he was only summoned when the Armenian and the khan’s Nestorian priests were on their way out, cross and censor and Gospels in hand. Sergius assured him that the baptism had gone through, and that although the khan was alternately attended by Christian, Muslim, and pagan priests, he really only believed the Christians. In the end, though, Mangu’s opinions proved to be, from the Franciscans’ point of view, depressingly pluralistic: “As God gives us the different fingers of the hand,” Mangu said, “so he gives to men several paths. God gives you the Scriptures, and you Christians keep them not … He gave us diviners, we do what they tell us, and we live in peace.” As for the Nestorian Christians, who were descendants of a sixth-century missionary effort launched by the patriarch of Constantinople, William had his concerns. They seemed unfamiliar with Scripture, a few of their priests embraced the dualistic Manichean heresy, and besides all that they drank too much, ate meat on Fridays, and feasted and washed themselves in the manner of their Muslim neighbors.

William and his companions longed to stay and minister to both the Nestorians and the non-Christians at Mangu’s capital, but once the weather was sufficiently warm, the khan sent them packing. After a year of hard travel, the remnants of the Franciscan expedition reached the Christian fortress of Acre, where William penned a letter to the French king reporting what he’d seen and heard. The news must have been disappointing: there were Christians in the East, but not of the proper sort; there were great kings, but the prospects for alliances with Christendom seemed unlikely. And Prester John? William said he had ruled in Central Asia, but had been destroyed by the Tartars generations ago. Twenty-five years later another traveler, a fellow named Marco Polo—one with, it should be noted, fewer qualms than William of Rubruck about embellishing his stories—reported much the same thing thing: Prester John was dead. To which Europe replied, “Long live Prester John!”

Most of us learned in school that medieval Europeans wanted spices because their food was so bad. But maggoty meat and moldy bread don’t fully explain the depth of the Western obsession with Eastern flavors. The social historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch notes that due to their cost, spices were most readily available to the rich—those who could also afford fresh or properly preserved foodstuffs. For wealthy Europeans, spices didn’t just make the meal palatable: they made the meal. Many medieval recipes read as if they’d been lifted from a modern Indian cookbook: large quantities of cloves, cinnamon, pepper, almonds, raisins, all in a single dish. At times spices were even a separate course—passed around on a tray and consumed a pinch at a time

Spices were so desirable, Schivelbusch says, because they offered Europeans “tastes of paradise”—flavors from a world outside their own. Spices provided a new and lush form of stimulation, a sign of the eternal, the transcendent, the wonderful. Contemporary illustrations of heaven often depicted spices and exotic plants. This growing awareness of and desire for goods from the East was born, somewhat ironically, out of the Crusades, where cultural domination mixed with cultural exchange. For soldiers, suppliers, and hangers-on, crusading amounted to a large-scale exposure to the products of the non-Western world. A motto of the times might have been Come for the Holy War, stay for dessert! So Europeans of the era may have found themselves feeling a bit conflicted. The East was the source of all sorts of wonders and exotica, the wellspring of the stuff of heaven. But the very region that seemed a sign of paradise was populated by peoples hostile, or at best indifferent, to the faith of the Western Christians. Could one condemn the East but still enjoy its products, or were all those tasty spices tainted by heresy? The answer to this conundrum may have manifested itself, among other ways, in the chaste but shadowy figure of—you guessed it—Prester John.

Which brings us to Sir John Mandeville, a fourteenth-century English knight who spent 34 years travelling “throughout Turkey, Armenia the little and the great; through Tartary, Persia, Syria, Arabia, Egypt the high and the low; through Lybia, Chaldea, and a great part of Ethiopia; through Amazonia, Ind the less and the more … and throughout many other Isles.” Around 1366, he penned, in Latin, French, and English, a widely read account of his journeys. Sir John’s narrative, like the man himself, seems to have been a ghostwriter’s fabrication—a means of collecting and connecting various reports, stories, myths, and fables from the Orient. Mandeville’s Travels devote an entire chapter to Prester John and his kingdom, incorporating most of the content of the original letter to the Byzantine emperor plus all sorts of new and captivating material—much of which gives credence to the idea that Prester John was beloved as proof that one could enjoy the wonders of the East and still be a pious Christian. Here, for instance, is Mandeville’s account of the royal bedroom:

“And all the pillars in his chamber be of fine gold with precious stones, and with many carbuncles, that give great light upon the night to all people. And albeit that the carbuncles give light right enough, natheles, at all times burneth a vessel of crystal full of balm, for to give good smell and odour to the emperor, and to void away all wicked airs and corruptions. And the form of his bed is of fine sapphires, bended with gold, for to make him sleep well and to refrain him from lechery; for he will not lie with his wives, but four sithes [i.e., times] in the year, after the four seasons, and that is only for to engender children With lavish decor, mood lighting, and burning incense, Prester John’s crib offered all the sensual pleasures Europeans loved in their stories of exotic East without the slightest hint of impropriety. A good Christian really could have it all. As with spices, wealth, and pleasant smells, so too with power. Most of the stories of Prester John hint at a deep European longing for a temporally omnipotent Christian leader. Part of this stemmed directly from the politics of the era: Christendom was becoming ever more divided, and defeats by Saracen and Mongol armies had called European power into question. Several of the expatriate Christians William of Rubruck encountered during his travels seemed convinced that Mangu Khan, once he converted, would be the longed-for leader to unify the world under Christ. But in Europe’s yearning for a Prester John was not just a lust for temporal power; it was an attempt to co-opt an ideology of power, to show that Christian might wasn’t just possible, it was the best sort. An Israeli historian named Meir Bar-Ilan has a Web page that notes a number of suspicious parallels between medieval European accounts of Prester John and of Alexander the Great—battles with elephants, pygmies, giants, a river that flowed from paradise, and so forth. What better way, after all, to argue that one could be as powerful as Alexander and still be Christian than simply to manufacture a Christian Alexander—and one so humble, incidentally, that he let no man call him King, but only priest or Presbyter. Now there’s no critique like self-critique, and it would hardly be fair to pronounce upon medieval Europeans’ reasons for telling and retelling the Prester John legend without considering why, more than 500 years later, I have decided to do the same. The short answer is probably the same one my ancestors would have given, if they’d had the words—it’s a cool story. It’s news from an exotic foreign realm, full of astounding creatures and untold treasures. For me the exoticism is one of time more than place, the marvels not Cyclopes or fountains of youth but curious spellynges and the strange details that filter down through the centuries But the other reason I’m so taken with the myth of Prester John is that I too have spent much of my life longing for a distant Christian king. I’ve yearned to discover fellow believers in unexpected places of power and influence. I’ve done this partly for reasons rooted in the faith: Christianity is by its own definition a message that needs to be shared. But I think I’ve sought to find, or to create, my own Prester John less for evangelical reasons than simply to affirm my own tastes and desires. I want to see Christian pop stars and politicians because, despite my misgivings about the world and its temptations, I find creativity, physical beauty, fame, and power to be pretty darn attractive. And what better way to sanction these attractions than to sanctify them, to imagine that there might be Christians at the center of all that gold and glitter? In high school I listened to the pop group Erasure and hoped against hope that when Andy Bell sang, “God is love / God is war / TV preacher tell me more / Father help me am I pure / Pure as pure as heaven?” it was a sign he was on the verge of getting saved. And though Erasure’s next album didn’t turn up on the shelves of my local Christian bookstore, I renewed my hope with a new song’s lyric that went, “I can see the old Cathedral, but I have to play it down.” Maybe Bell was on my team, just undercover—which was, in a way, even more exciting. It took still another album, Abba-esque , before I was finally and thoroughly convinced that Erasure were more interested in cross—dressing than in crossing over to Christian music. In and after college, as tends to happen, my quest put on more sophisticated airs, as I debated the merits of various movies my friends and I suspected of being crypto-Christian in message: The Shawshank Redemption, Contact, and of course The Matrix. I’ve spent hours surfing the Web in an attempt to figure out just where Fight Club director David Fincher stands, faith-wise. And after a particularly moving viewing of The Color of Paradise at the local art cinema, I spent the next week trying to convince myself that the film’s Iranian director, Majid Majidi, might be a Christian. This, for me, was the easier philosophical leap than considering that a Muslim filmmaker might have something to teach me about God. I thought that my concerns for the state of a pop singer’s soul, my rejoicing when I saw a film that presented a message of grace to a secular audience, were signs that I was rejecting the superficiality of popular culture in favor of spiritual depth. Perhaps I was. But I think those concerns also revealed my need to mediate between the God I love and the stuff I like. As with most fantasies, I’ve found that the search for true believers in unexpected and exciting places is usually far more exciting than the discovery. Once you’ve cornered your elusive, praying prey, they generally turn out to be disappointingly human. They swear or smoke, are sometimes depressed or divorced. And even the grace—given few who wield both fame and orthodox Christian faith wind up astounding us, not with how much they can do, but with how ineffectual they sometimes seem. Unlike the gilded bed of a certain priest-king from the East, the trappings of fame do not, as best I can tell, make for easier sleep, nor do they drive away temptation. The lure of worldly Christian success, whether I desire it for myself or for others, is strongest when the object of my dreams is just out of reach, just over the horizon. It’s much easier to dream of Christians in positions of power and influence than to realize that they’re already there, and just aren’t as impressive as I’d imagined. The myth of Prester John persisted precisely because he couldn’t be found. And, in fact, once Europeans did discover a Christian king who answered to that name, they quickly lost interest. So back to our story. After the collapse of the Mongol empire, Prester John’s coordinates became more and more erratic. A map published in 1375 places him in the East Indies. One from 1407 has him in the Caucasus mountains. But by the end of the fifteenth century, more and more accounts placed the priest-king in Africa, somewhere near the source of the Nile. In 1487 King João of Portugal sent two explorers, Affonso de Paiva and Pedro da Covilhão, to find Prester John and, while they were at it, learn what they could about the geographies of, and opportunities for trade with, both Africa and India. Neither made it back to Portugal, though Pedro did manage to post from Cairo an encouraging letter to the king detailing the Indian ocean trade in spices and luxury items. He then disappeared into the African interior

> wikipedia In 1498 Vasco de Gama, on his famous voyage around Africa to India, put in at Mozambique and was told by Arab traders that Prester John resided somewhere inland. Twenty years later another group of Portuguese reached the court of Lebna Dengel, the Christian king of Ethiopia, and decided he must be the priest-king of legend. Being a man of many titles, Lebna Dengel happily agreed to take on one more, and thus, after all those centuries, Prester John was finally crowned. Attendant at John’s court—surprisingly or not, depending on how you look at it—was old Pedro da Covilhão, long assumed dead. He had been welcomed into Ethiopia but forbidden to leave, so he’d married, settled down, and made the best of it. For some reason, the exit restriction was not extended to the new arrivals, so the expedition’s chaplain, Father Francisco Alvares, made it home to tell the Western world the long-awaited news of Prester John and his kingdom of mud huts. But by then, Europe’s attention was elsewhere. The new object of European desire and fantasy was, of course, that distended blotch on the left-hand side of Martin Waldseemüller’s famous map: the New World. All the old legends of pygmies and Amazons, golden cities and rivers flowing from paradise quickly found new lodgings in Amerigo’s lands. The priest-king faded from view, though it would be longer still before European culture finally exorcised the temptation to write, when confronted with a source of exotic wonder or a blank space on the map, “Here be Christians.” For instance: in 1805 the Lewis and Clark expedition, bound overland from the Mississippi to the Pacific, kept a watchful eye for a legendary tribe of white-skinned, Welsh-speaking Indians, descendants of a colony founded in 1070 by a Welsh prince named Madoc. And in 1827 a New Englander named Joseph Smith laid down the precepts of an entire religion—Mormonism—which grew from the theory that the great civilizations of pre-Colombian America had been Jewish, and then Christian. And so it goes. A few years ago, I spent a pleasant afternoon on ahilltop near the South Indian city of Chennai. At the crest is a small church, the altar of which signifies the exact spot where one of Jesus’ disciples, the apostle Thomas, was martyred in 78 A.D. There’s a stone cross said to have been carved by Thomas, and, above the altar, a lovely portrait attributed to Saint Luke, painted in a style one usually associates with later centuries. I’m not sure how much of what I saw that day would pass the scrutiny of modern scholars, or even that of the man who refused to believe in Christ’s resurrection until he placed a finger in his wounded side But there have been communities of Christians there and in the neighboring state of Kerala, if not since the first century then at least since the sixth, when missionaries from the Syrian church arrived. Much the same can be said for nearly all of the realms inhabited by Prester John during his 500 years of fame. Coptic missionaries started churches in Ethiopia and Nubia by the fifth century. The Nestorians traveled as far as China by the seventh century, where they seem to have briefly enjoyed the favor of the Tang dynasty. So I stood on Saint Thomas Mount, in the slanting sunlight, wondering just where the proper boundary lies between playing the skeptic and being open to wonder. The answer of course is that I don’t know, and even if I did, tomorrow the map might well be redrawn. What amazes me about the stories of Prester John is not how false they proved to be, but how true. There were Christians, and even Christian kings, in Africa and Asia. Therwas even a great Eastern city, Constantinople, ruled by a Christian patriarch and filled with wealth said to be unmatched anywhere in the world. I still dream of priest-kings past and present, though these days I dream with caution, realizing that I may not be the best judge of my own motives, nor will I always recognize it when my dreams come true. Constantinople, after all, was sacked and looted by the Christian knights of the fourth Crusade, not 60 years after Europeans first heard the name of Prester John