cc Andrew Mason/flickr

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, by Dave Eggers (Simon and Schuster, 2000), 375 pp., $23.00

This is a book review. As such, it will make the pretense of being primarily about the book in question. But as the reviewer pursues the task of informing you, the reader (hi!) whether, and in what ways, the book in question is good, or bad, or interesting, he is also working towards a second end, which is to let you know that the reviewer’s own ideas are, in fact, both good and interesting—perhaps even more interesting than the aforementioned book. And so, fair reader, be warned: for although this review may attempt to weave together common threads, citing the odd example in order to reveal, with astute and impeccable logic, what a certain four-hundred-page tome says and means, both in itself and as it concerns the life and ideas of its author (who is only in his late twenties, and may yet change his mind), it is still the work of a reviewer who is himself only in his middle twenties, who still has a lot to learn, and—in truth—who harbors the secret hope that the book’s author will one day read this review, and be so impressed, or moved, as to beg the reviewer to come and write for his current magazine, or will maybe want to hang out sometime. Ahem

It is difficult to criticize A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers’s thoroughly postmodern memoir, not so much because of the touchy subject matter (the struggles of the newly orphaned) as because the book is so full of confessions and qualifications as to render further comment pretty much unnecessary. A Heartbreaking Work concerns Eggers’s life in the years after, at age twenty-two, he lost both parents to cancer, and was left on his own (more or less) to raise his eight-year-old brother, Toph. The story is a necessarily poignant tale of grief and fear and the overcoming thereof, interwoven with accounts of Eggers’s own attempts to find a voice for himself, his friends, and his generation, as charted by the rise and fall of Might magazine—the mid-’90s satirical-ironical-idealistic voice-of-the-nation’s-young-people publication that Eggers co-founded. (He currently edits another magazine, McSweeney’s , a smart Brooklyn-based literary quarterly.) Underlying all of the specifics of Eggers’s story is a consistent foundation of self-critique, knowing asides, and, of course, knowingly self-aware criticisms of all the self-critique. Although Eggers uses ironic devices expertly and thoroughly, his memoir doesn’t exactly qualify as a work of Irony as it’s come to be defined and derided by Jedidiah Purdy (For Common Things) and his ilk. There is very little flip Seinfeld-style sarcasm; instead Eggers favors a sort of abortive irony that somersaults immediately back into sincerity and leaves you standing, feet firmly planted, but breathless and a bit dizzy. He’s not above changing the facts for the sake of literature, but he conscientiously points out which names he’s changed, how the narrative’s been reshuffled for the sake of flow, and which sections of dialogue have been modified to keep the participants from sounding like idiots.

In thirty-nine pages of prefaces, acknowledgements, and “Rules and Suggestions for the Enjoyment of this Book,” Eggers outlines and deconstructs twenty-two major themes of the memoir, provides a helpful guide to most of the symbols he’s used (moon = father, et cetera), and lists which pages readers in a hurry might just as well skip over. The prefaces highlight Eggers’s second, and perhaps more effective ironic maneuver: the transmutation of mockery into wonder. The section is at once a satire of, and an homage to, the quirks and intricacies of publishing, bookbinding, typography, and prose ranging from nineteenth-century nonfiction to the novels of Tom Clancy. You quickly get the sense that for Eggers, the questions, Isn’t this silly and pointless? and, Isn’t this deep-down amazing and wonderful? really aren’t that different. In a page-long apology for the book’s title, Eggers writes:

cc Andrew Mason/flickr

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, by Dave Eggers (Simon and Schuster, 2000), 375 pp., $23.00

This is a book review. As such, it will make the pretense of being primarily about the book in question. But as the reviewer pursues the task of informing you, the reader (hi!) whether, and in what ways, the book in question is good, or bad, or interesting, he is also working towards a second end, which is to let you know that the reviewer’s own ideas are, in fact, both good and interesting—perhaps even more interesting than the aforementioned book. And so, fair reader, be warned: for although this review may attempt to weave together common threads, citing the odd example in order to reveal, with astute and impeccable logic, what a certain four-hundred-page tome says and means, both in itself and as it concerns the life and ideas of its author (who is only in his late twenties, and may yet change his mind), it is still the work of a reviewer who is himself only in his middle twenties, who still has a lot to learn, and—in truth—who harbors the secret hope that the book’s author will one day read this review, and be so impressed, or moved, as to beg the reviewer to come and write for his current magazine, or will maybe want to hang out sometime. Ahem

It is difficult to criticize A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers’s thoroughly postmodern memoir, not so much because of the touchy subject matter (the struggles of the newly orphaned) as because the book is so full of confessions and qualifications as to render further comment pretty much unnecessary. A Heartbreaking Work concerns Eggers’s life in the years after, at age twenty-two, he lost both parents to cancer, and was left on his own (more or less) to raise his eight-year-old brother, Toph. The story is a necessarily poignant tale of grief and fear and the overcoming thereof, interwoven with accounts of Eggers’s own attempts to find a voice for himself, his friends, and his generation, as charted by the rise and fall of Might magazine—the mid-’90s satirical-ironical-idealistic voice-of-the-nation’s-young-people publication that Eggers co-founded. (He currently edits another magazine, McSweeney’s , a smart Brooklyn-based literary quarterly.) Underlying all of the specifics of Eggers’s story is a consistent foundation of self-critique, knowing asides, and, of course, knowingly self-aware criticisms of all the self-critique. Although Eggers uses ironic devices expertly and thoroughly, his memoir doesn’t exactly qualify as a work of Irony as it’s come to be defined and derided by Jedidiah Purdy (For Common Things) and his ilk. There is very little flip Seinfeld-style sarcasm; instead Eggers favors a sort of abortive irony that somersaults immediately back into sincerity and leaves you standing, feet firmly planted, but breathless and a bit dizzy. He’s not above changing the facts for the sake of literature, but he conscientiously points out which names he’s changed, how the narrative’s been reshuffled for the sake of flow, and which sections of dialogue have been modified to keep the participants from sounding like idiots.

In thirty-nine pages of prefaces, acknowledgements, and “Rules and Suggestions for the Enjoyment of this Book,” Eggers outlines and deconstructs twenty-two major themes of the memoir, provides a helpful guide to most of the symbols he’s used (moon = father, et cetera), and lists which pages readers in a hurry might just as well skip over. The prefaces highlight Eggers’s second, and perhaps more effective ironic maneuver: the transmutation of mockery into wonder. The section is at once a satire of, and an homage to, the quirks and intricacies of publishing, bookbinding, typography, and prose ranging from nineteenth-century nonfiction to the novels of Tom Clancy. You quickly get the sense that for Eggers, the questions, Isn’t this silly and pointless? and, Isn’t this deep-down amazing and wonderful? really aren’t that different. In a page-long apology for the book’s title, Eggers writes:

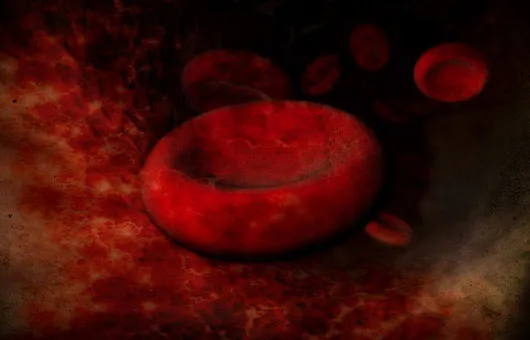

In the end, one’s only logical interpretation of the title’s intent is as a) a cheap kind of joke b) buttressed by an interest in lamely executed titular innovation (employed, one suggests, only to shock) which is c) undermined of course by the cheap joke aspect, and d) confused by the creeping feeling one gets that the author is dead serious in his feeling that the title is an accurate description of the content, intent, and quality of the book Through all the asides and witticisms, through layer upon layer of cheap (if well-crafted) jokes, Eggers is in fact dead serious—desperate to have his story heard, to be loved for it, by it, and through it, and wholly aware of the foolishness and obviousness and awkwardness of that desperation. He wants to rip out his still-beating heart and put it on display for all to see, but then spends most of his time fussing about the display case which will house the throbbing, bloody organ. The distraction technique works, for a while. But blood runs through this book—the post-preface narrative begins with a nosebleed (a life-threatening condition for Eggers’s mother, then in the late stages of stomach cancer), and ends in a metaphorical crucifixion (on the beach, while tossing a frisbee—more on this later). Blood is the life-force Eggers sees drained through freak accidents and deaths—his parents’ twin terminal cancers, the macabre suicides of several neighbors in the posh Illinois suburb where he grew up, and the head traumas, fatal infections, and self-destructive urges which beset his current set of friends. It’s no wonder that Eggers is so desperate to undercut the sources of his fears, to analyze and annihilate the guilt and terror that ever threaten to drag him under, and to connect with something larger and more stable than himself. He longs for redemption—he wants his grief and his hope to be given meaning. He needs a reason not to fear. And although a nominal Catholic background has given him enough of a moral framework to … well, feel guilty, Eggers looks elsewhere for the protection he requires. As a child, he once painted life-size superheroes on his bedroom walls to protect himself from vampires as he slept; after his parents’ death, Eggers finds inspiration in the beauty and virility (in a pre-teen sense) of his younger brother. His love for, and belief in, Toph slices through the dread at certain sunnier moments, and life again glints with true and solid beauty. But the flashes never last long. A sweetly poetic description of a game of frisbee with Toph is quickly overshadowed by Eggers’s fears: We throw so far, and with such accuracy, and with such ridiculous beauty … When I run I can feel the contracting of my muscles, the strain of my cartilage, the rise and fall of pectorals, the coursing of blood, everything working, everything functioning perfectly, a body in its peak form, albeit on the thin side, just a bit shy of normal weight, with a few ribs visible, which, come to think of it, might look weird to Toph, might look kind of anemic, might frighten him, might remind him of our father’s weight loss .. For a while Eggers pursues a talk-show model of redemption—the notion that if he tells enough people his story, the pain and sorrow will somehow be dissipated. Midway through the book, he takes a shot at this sort of salvation by auditioning for a spot on MTV’s The Real World. The interview for the show, recounted in an ever-more-fictionalized, psychoanalytic style, is for Eggers a first, failed attempt at transcendence. He wants desperately to be selected, to be chosen as a tragic spokesmen for his generation, for he sees in that chosenness a chance to be at the center, to be connected, in community, to be, as he puts it, “the strong-beating heart that brings blood to everyone.” But even after all that soul-baring, MTV passes him over—an aspiring cartoonist gets the Real World slot. I think it’s fair to say that this review is going well. Doing a good job of really involving itself with the book, really caring about the author and his predicaments, his fears and hopes and obsessions with certain bodily fluids. Even mimicking his very prose in a sort of self-aware-and-thus-ironic homage. But what remains, of course, is the kicker: the ending that ties it all together, that leaves the reader (are you still there?) thoughtful, ready to say Ah-ha! when the book comes up in conversation— Ah-ha! I’ve just read a review of that book, and—this is the interesting thing—it said that .. Eggers’s story ends with a crucifixion—to be precise, with his own crucifixion. It is, actually, a rather subtle undertaking, flowing stream-of-consciously out of yet another beautifully unironic passage of frisbee-as-blank-verse. Eggers begins musing about his generation again, about his longing to be saved by and through his connection to others like him—those who are young and alive and disillusioned and hopeful. But this time he doubts their listening, saving ears. They are not a part of him; they are after his blood, yes, but as sacrifice, not circulation. They will not save him. Talking won’t ease the pain: only shed blood offers redemption. He cries out to his betrayers, “I am somewhere on some stupid rickety scaffolding and I’m trying to get your stupid fucking attention because I am willing and I’ll stand before you and I’ll raise my arms and give you my chest and throat and wait, and I’ve been so old for so long, for you, for you, I want it fast and right through me—” In this imagined death, Eggers offers a powerful, but incomplete reflection on blood atonement. All that’s absent is the divine—which is why the crucifixion-cum-epiphany cannot stand on its own, why in the end there must be more undercutting, more knowing asides, more Rules and Suggestions for the Enjoyment of This Book. Eggers ends in hope, rather than nihilism, because he senses a sort of wonder and life beneath the suffering—something more than human. And that is, maybe, the one thing that Eggers cannot describe, define, defuse, and wittily dissect