I love cliches and hackneyed expressions of every kind, because they’re largely true. The thousands of such cliches and hackneyed expressions that our language has bequeathed us are a strong treasure trove of human insight and knowledge.

—Violet Wister (Greta Gerwig) in Whit Stillman’s Damsels in Distress, 2011

The ‘cliché’ metaphor, by the way, is itself becoming a ‘cliché’, so stereotyped do we grow in protesting against the stereotyped.

—Israel Zangwill, “Romeo and Juliet and other Love Stories,” 1895

What is it that makes the output of large language models and other varieties of generative AI so interesting, and then so boring? For me the most useful operative metaphor for AI’s promise and problems is the cliche. Appropriately, the initial thought is certainly not original to me (I think I picked it up from Andy Crouch), and is certainly not the only one out there. AI output is like infinite interns, or it’s a blurry jpeg of the Web, a system for delivering what an answer probably looks like but not what it is, or it’s simply slop that gets ever more tepid with everything it touches.

But the cliche, I can work with. When I type a prompt into the box, I think of it not as “give me XYZ” but “give me a cliche for XYZ” and my expectations feel more calibrated. Oftentimes a cliche really is what we want. It certainly is when I’m getting help for little coding projects — I’m not going for originality in my excel formulas — or refreshing my notion of the general form a cover letter, or a play dialogue, or the page of a prayer book, or a 19th century advertisement for cold medicine might look like. When I remember I’m asking for a cliche, I’m not that sad to get it, and I can actually be delighted for a bit of what form the cliche can take, especially when XYZ is a half-formed notion just waiting to be riffed.

Up until a year ago I would have assumed that cliche slipped into English like ennui, as an Old French term in the category of “things that are kind of bad but not terrible.”

But the cliche has always had technological ties, ties to what one might term the accelerating and proliferating experience of modernity. It was originally a printing term — its original OED definition ties it with another term of art that also escaped that world: “stereotype block (1809)”. Its original formation was likely onomatopoeic, a description of the clicking noise made in a technical process (see also: Kodak).

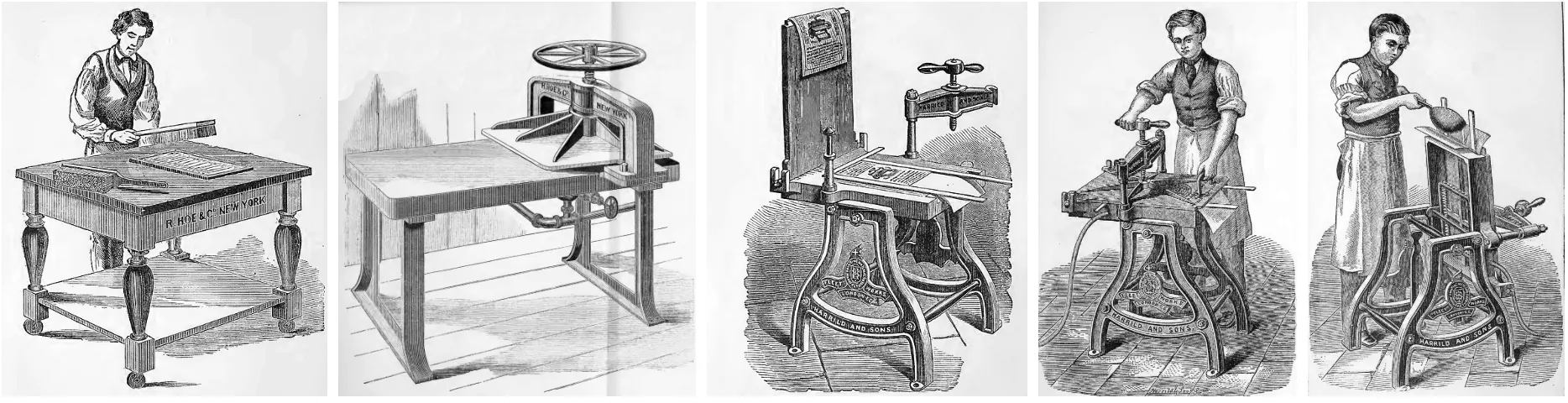

Using a forme of typecast sorts to mold a flong to cast a stereotype cliche (from Frederick J. Wilson’s Stereotyping and Electrotyping (1880), via wikipedia)

Using a forme of typecast sorts to mold a flong to cast a stereotype cliche (from Frederick J. Wilson’s Stereotyping and Electrotyping (1880), via wikipedia)

So. A Cliche is a stereotype block, which is to say, literally a copy of a copy of a copy: you start with a source document, you typeset its individual letters in a printing frame, you make an impression of that frame with a piece of quasi-papier-mache called a flong (a term of art that definitely did not escape that world!), then dry out your flong and pour liquid metal into it, creating a positive mold of the typeset piece. And that, then, is what you use to make your printed pages (that is, copies of a copy of a copy of a copy).

The cliche took on photographic airs (as a “negative cliche”) around 1850, and seems to have escaped into metaphor only around sometime between 1869 and 1881. By 1895 the English playwright Israel Zangwill, who would go on to give us the molten-metal cliche of the melting pot metaphor of assimilation, was, per the quote above, already growing tired of it.

If what LLMs are best at (and indeed if it’s really the only thing they do) is give us cliches, then it might be helpful to bear in mind the link between the cliche as social artifact and the cliche as technological artifact. Cliches are, per the Whit Stillman quote at the top, shorthand encodings for larger bits of human culture (and even the subset we might call wisdom), prone to falling flat and being dismissed, but still supremely useful if you deploy them with skill.

When I prompt an LLM for a bit of code (or these days, a full functioning website) what it gives me is a cliche of functional software. Which is kind of what I want: what is the expected way of fleshing out my prompt, one of the main expectations being that it should actually work.

When I ask an LLM for a poem, it gives me a cliche of poetry; more and more it’s an actual good cliche, with well-working syntax, expected imagery, the everyday emotional beats. The best LLM poems are, to my eye, where the prompt challenges the LLM to output something that isn’t a cliche at all (e.g. an absurdist improve prompt), and thus it’s a little triumph when the LLM says, “see, here’s the most cliche’d version possible of a sonnet about the krebs cycle written with maximum Australian slang.”

While I was preparing this website for relaunch, I came upon an old thing I had quote-blogged 15 years ago, from Umberto Eco’s essay on the miraculous efficacy of the film Casablanca:

Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred clichés move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves , and celebrating a reunion. Just as the height of pain may encounter sensual pleasure, and the height of perversion border on mystical energy, so too the height of banality allows us to catch a glimpse of the sublime. Something has spoken in place of the director. If nothing else, it is a phenomenon worthy of awe.

It may only rarely be so, but may it be so.